Author: Felix Schürholz, DecisionTiming.com

Published Online: March 16, 2018

Felix Schürholz

Decision Coach

Abstract: Presentation of an integrated model for motivation and self-efficacy in decision making (ME-DM) applying a dual process theory mindset

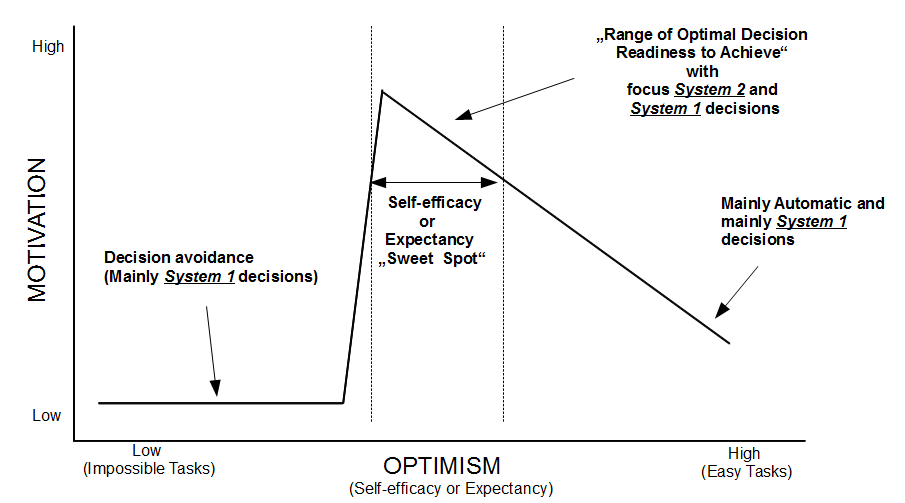

The (ME-DM) model contends that a nonmonotonic and discontinuous function best represents the relationship of “motivation and self-efficacy in decision making”. It suggests that there is an optimal range of self-efficacy level (System 2 Focus) and self-efficacy strength (System 1 Focus), where optimal learning and optimal decision making, for important and irrevocable decisions, is most promising. The model explores, how and why we decide in certain situations and how decision making, beliefs and learning are connected.

Keywords: Motivation, Self-efficacy, Expectancy, Decision Making, Decision Avoidance, Self-regulation, Goals, Dual process theory, Triple process theory, Learning, Belief

Acknowledgment: The “ME-DM” model presented here builds essentially on three main areas of research and discovery. 1) Motivational Theory. 2) Goal Setting, Self-Regulation and Self-Efficacy. 3) Dual Process Theory, Judgment and Decision Making (JDM). The references chosen in the article below represent my attempt to express my gratitude for the respective contributions of the authors and researchers listed.

Pre-publication: 19th June 2017

Publication: 16th March 2018

Publisher: www.decisiontiming.com

Full Paper: Download PDF here

Figure 1: Integrated model for motivation and self-efficacy in decision making (ME-DM), (Schürholz, 2017/2018)

Introduction

The question why we decide not to decide (Anderson, 2003), why we sometimes decide sub-optimally (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 – Baumeister, 2003 – Ariely, 2008) or why we often decide automatically (Moore & Lowenstein, 2004 – Klein, 2009) has been at the focus of the study of judgment and decision making for many decades.

Faced with this large spectrum of decision behavior and decision quality, two schools “Heuristics and Biases Approach” (Meehl, 1954 – Tversky & Kahneman, 1971) and “Naturalistic Decision Making Approach” (deGroot, 1946/1978 – Chase & Simon, 1973) have formed. You could also call these two intellectual traditions – “models”, as Klein (2009) does, when he refers to “the human-as-hazard model… [and] …the human-as-hero model”.

Following the tradition of Kahneman & Klein (2009) in trying to reconcile these two different views, I will present in this article an integrated model for motivation, self-efficacy and decision making that offers the opportunity “to map the boundary conditions that separate true intuitive skill from overconfident and biased impressions”.

One area that Kahneman & Klein pointed to namely “task environments of “high-validity” and “zero-validity”” provide a very practical condition for this mapping.

K & K focus on high validity task environments defined by “stable relationships between objectively identifiable cues and subsequent events or between cues and the outcomes of possible actions.” They suggest that “medicine and firefighting are practiced in environments of fairly high validity.” For zero validity environments, they state that “outcomes are effectively unpredictable”. The examples they provide are “predictions of the future value of individual stocks and long-term forecasts of political events”.

To be able to map the perspective of the expert onto the perspective of the ordinary decision maker, I will refer to task environments of high-validity as “Easy Tasks” and task environments of zero-validity as “Impossible Tasks”.

In acquiring knowledge, experience, skills, methods and tools, the boundaries of what was previously “impossible or easy” of course changes.

The point to note though from the subjective experience of the individual decision maker, there will always be and remain an “impossible and easy decision task environment”, while the content and discipline of those environments might change.

This leads me to the general and integrated model for motivation and self-efficacy in decision making (ME-DM) that I am presenting here. Such a model, at an initial stage, to describe a human decision maker, of course, needs to refer to the most basic aspects of the human mind, namely the conscious and unconscious part (see dual process theory below). Generally we just tend to focus on one or the other when it comes to decision making. Here I attempt to focus on both.

Dual process theory

According to (Evans, 2008) the most neutral terms to use for the two different modes of processing in dual process theory are System 1 and System 2 processes (Kahneman & Frederick 2002, Stanovich 1999). Evans concludes: “Almost all authors agree on a distinction between processes that are unconscious, rapid, automatic, and high capacity [System 1], and those that are conscious, slow, and deliberative [System 2]”.

“Other recurring themes in the writing of dual-process theorists are that System 1 processes are concrete, contextualized, or domain-specific, whereas System 2 processes are abstract, decontextualized, or domaingeneral.” (Evans, 2008)

Authors like (Evans 2006, Klaczynski & Lavallee 2005, Stanovich 1999) “assume that belief-based reasoning is the default to which conscious effortful analytic reasoning in System 2 may be applied to overcome.”

(Evans, 2006) proposed “that heuristic responses [System 1] can control behavior directly unless analytic reasoning [System 2] intervenes. In other words, heuristics provide default responses that may or may not be inhibited and altered by analytic reasoning.” This System 2 intervention is more likely according to (Stanovich, 1999) “when individuals have high cognitive ability or a disposition to think reflectively or critically.”

By presenting the “Integrated model for motivation, self-efficacy and decision making” (ME-DM) I like to suggest that this System 2 intervention is in fact a function of perceived and chosen task difficulty, context motivation, self-efficacy as well as ease (and capacity) to apply System 2.

The model that describes this function best is the Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous Model of Self-efficacy (Vancouver et al., 2008 – Schürholz, 2017 – Prepublication).

I hope that this model lives up to the challenge posed by (Evans, 2003) to “show how such two distinct systems [System 1 and System 2] interact in one brain and to consider specifically how the conflict and competition between the two systems might be resolved in the control of behaviour.”

You should note that it is very likely that in the not so very distant future, we will not only be talking about System 1 and System 2, but presumably also about a distinct System 3, located in and communicating with our second brain, the enteric nervous system (ENS). The changes that I am talking about can be attributed to the findings and influence of what is termed the Microbiome (Gershon, 1998 – Collins, Surette & Bercik, 2012 – Tillisch et al. 2013 – Rao & Gershon, 2016). I like to refer to the functionality of this System 3 as the process of “influencing”.

As we have no general understanding of a triple process theory yet though, let us stay with the dual process theory in this paper and for the time being.

… (Break for Short Version), You can download the full paper here …

The Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous Model of Self-efficacy with respect to Decision Making

What is “Self-efficacy”? Self-efficacy is a type of expectancy (Olson, Roese, & Zanna, 1996) related to an individual’s belief that he or she can organize and execute the actions necessary to achieve given levels of performance (Bandura, 1977). What is unclear though, under what condition and to what extent, different levels of self-efficacy, effect changes in behavior (Task/Action) and motivation (Resource Allocation). In 2008, (Vancouver et al.) reviewed several possible relationships between self-efficacy and motivation. Focusing on 4 empirical models (Positive Model (Kanfer, 1990 – Beach & Connolly, 2005), Negative Model (observed by Bandura, 1997 – Bandura & Locke, 2003), Inverted-U Model (Atkinson, 1957 – Kanfer & Ackerman, 2004) and Discontinuous Model (Kukla, 1972 – Carver & Scheier, 1998)) they suggested, and eventually confirmed, one integrated model that could reconcile the various empirical models examined, over a wide range of task difficulty. The model they suggest is a Nonmonotonic, Discontinuous Model (see below). I believe this model is particularly relevant to the special and unique task of decision making.

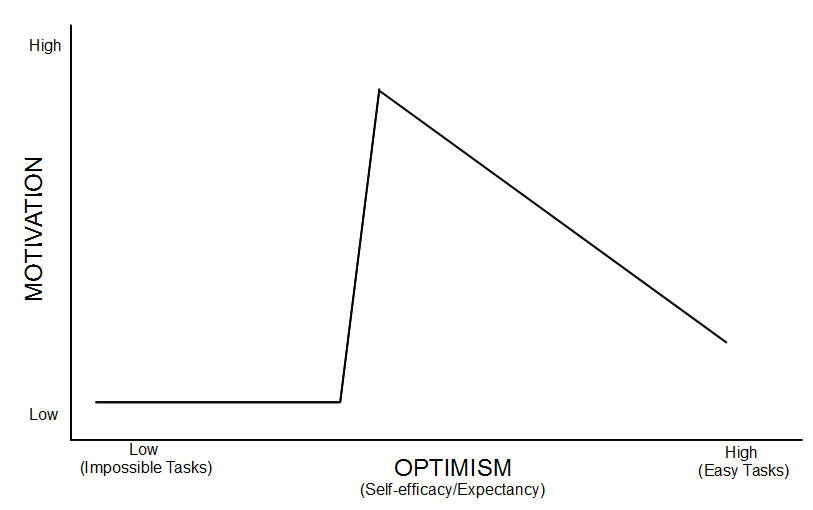

Figure 2: Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous Model of Self-efficacy (Version Schürholz, 2017)

While their model and article has been cited 182 times to date, there is probably still a long way to go until it is generally accepted for most tasks. While it might not apply to all tasks under all circumstances, I believe it is particularly well suited to describe the special motivation and task relationship for decision making. I will briefly point out the elements of their argument (Vancouver et al., 2008) that should be noted for a Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous model:

a) Reasoning by (Kukla, 1972), “Kukla argued that if one felt that success was unachievable, one would not even try. However, if one attributed task performance to one’s inputs (i.e., effort and ability), Kukla predicted that one would allocate effort commensurate with one’s perceived ability, such that the greater one’s perceived ability at the task, the less effort one would exert. That is, individuals would allocate effort to compensate for perceived ability if they thought effort mattered. Thus, Kukla argued that when perceived ability is very low, no motivation is exhibited because one chooses not to engage in the behavior. As perceived ability increases, a sudden jump in motivation occurs because there is now sufficient expected utility in the behavior to make it worth engagement. If engaging, however, the intensity of one’s efforts is inversely related to perceived ability because less effort is deemed necessary if ability is high.”

b) When the maximum motivation is reached: “However, should one choose to engage, the magnitude of resources allocated drops from its high at this point of discontinuity to lower levels as higher self-efficacy beliefs lead one to anticipate fewer resource needs.”

c) Evidence for the model: “Kukla (1972) provided some evidence to support his model, but most of the evidence comes from Brehm and colleagues (i.e., Brehm & Self, 1989; Wright & Brehm, 1989). Specifically, Brehm, working from Kukla’s model, developed a theory of energization that articulates a nonmonotonic, discontinuous function for motivation based on the perceived difficulty of the task. Because Brehm’s theory conceptualizes motivation as arousal, studies to test energization theory typically examine cardiovascular responses (e.g., heart rate) during impossible, difficult, and easy conditions (Wright, 1996). The research generally has found that heart rate and systolic blood pressure are highest in the difficult condition and lower in the impossible and easy conditions, thus supporting a nonmonotonic model.”

It should be noted at this point that the arguments a) – c) by (Vancouver et al., 2008) only describe strictly speaking the shape of the relationship of arousal to ability (or task difficulty). Whether this also represents the relationship of motivation to self-efficacy very much depends on the definition of self-efficacy. In an exchange of argument between Bandura (2012, 2015) and Vancouver (2012) the question of the properties and definition of self-efficacy and particularly the so-called negative effect (the downward slope), were discussed in detail.

The main points of the discussion regarding the negative effect can possibly be summarized as follows:

● “Because of the multidetermination and contingent nature of everyday life, human behavior is conditionally manifested. Hence, no factor in the social sciences has invariant effects.” (Bandura, 2012)

● “Social cognitive theory does not allege an invariant self-efficacy effect. Indeed, it explicitly specifies a variety of conditions under which self-efficacy may be unrelated, or even negatively related, to quality of psychosocial functioning (Bandura, 1997).”(Bandura, 2012)

Those conditions can be:

● Mismatch between assessed self-efficacy and the activity domain (Bandura, 2012)

● Self-efficacy during acquisitional phases (Bandura, 2012)

● Self-efficacy can negatively relate to resource allocation during or while planning for task performance

(Vancouver, 2012)

● Self-efficacy on planned and reported study time prior to an exam (Vancouver, 2012)

● Ambiguity about the performance undertakings (Bandura, 2012)

● Situational constraints (Bandura, 2012)

● In performance situations in which misjudgment of capability is inconsequential (Bandura, 2012)

● Miscalibrated self-efficacy (e.g., overconfidence) (Vancouver, 2012)

● Self-efficacy belief may also diverge from action because of genuine faulty self-appraisal.(Bandura, 2012)

The integrating aspect of the discussion between Bandura and Vancouver might be, it “is not that we make different predictions, but that we have different explanations for the negative effect” as Vancouver (2012) states.

As far as decision making goes, the discussion of boundary conditions where self-efficacy either relates positively or negatively to this unique task, is particularly applicable. I mentioned above (under Task Motivation and Decision Motivation) that there are three boundary conditions that are especially significant and connected with decision making namely its “preparatory nature“, the intrinsic ambiguity & uncertainty of outcome, as well as the complexity & interrelatedness of decisions.

If you have a look at the above arguments of Bandura and Vancouver you can easily identify the relevance of these special conditions (i.e. for acquisitional phases, planning for task performance, overconfidence and situational constraints) thereby strengthening and supporting the application of the Nonmonotonic, Discontinuous Model for the process of decision making.

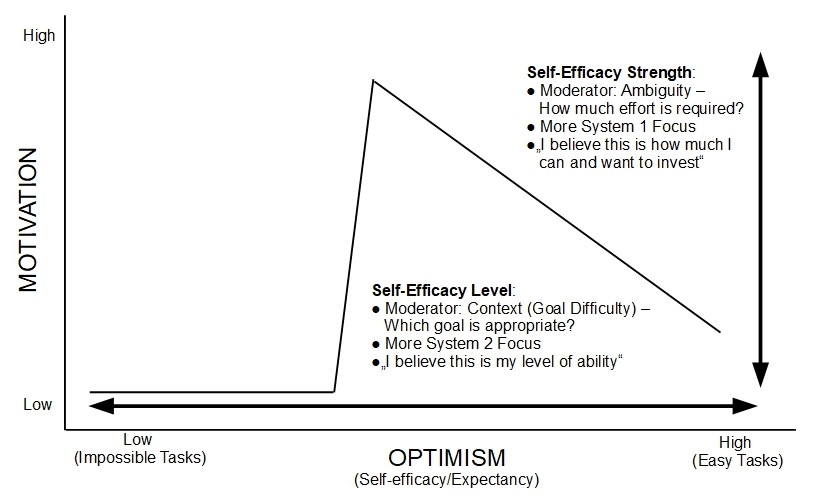

There are two further studies, that provide evidence for the Nonmonotonic, Discontinuous Model. One is by Schmidt & DeShon (2010) with respect to Ambiguity, and the other by Beck & Schmidt (2012) with respect to Context (Goal Difficulty).

I like to discuss these papers in more detail because they allow to analyze the two dimensions of self-efficacy defined by Bandura & Locke (2003: 96) “perceived self-efficacy is measured in terms of judgments of personal capabilities and the strength of that belief” (2003: 96). Vancouver (2012) interprets this definition as follows: “Bandura claims that self-efficacy beliefs can be described in terms of level and strength. Level, also called magnitude, is the primary dimension of self-efficacy, much like goal difficulty is the primary dimension of goals. Bandura often describes it in terms of the level of performance one thinks oneself capable of reaching in a given context. Strength is more difficult to pin down. It seems strength of belief refers to one’s confidence in the belief. That is, strength should predict how well the belief stands up to disconfirming information, similar to the way goal commitment predicts an individual’s perseverance in relation to a goal.”

Drawing on these two sources I offer a slightly new definition for self-efficacy (see below) where I incorporate dual process theory as well as the moderators of Ambiguity examined by Schmidt & DeShon (2010) and Context (Goal Difficulty) investigated by Beck & Schmidt (2012), see below.

Figure 3: Definition for Self-Efficacy Level and Self-Efficacy Strength (Schürholz, 2017/2018)

As indicated, using the above definition for Self-Efficacy Level and Self-Efficacy Strength I will discuss in more detail the papers of Schmidt & DeShon (2010) and Beck & Schmidt (2012) examining the relationship of motivation (in terms of performance, resource allocation or self-reported effort) to self-efficacy, in tasks, that can be compared to decision making. The findings and insights generated will be used to further develop and detail the ME-DM equation, as well as to highlight different decision situations of varying decision difficulty.

… (Break for Short Version), You can download the full paper here …

3.1) Challenge of decision making under conditions of high self-efficacy level

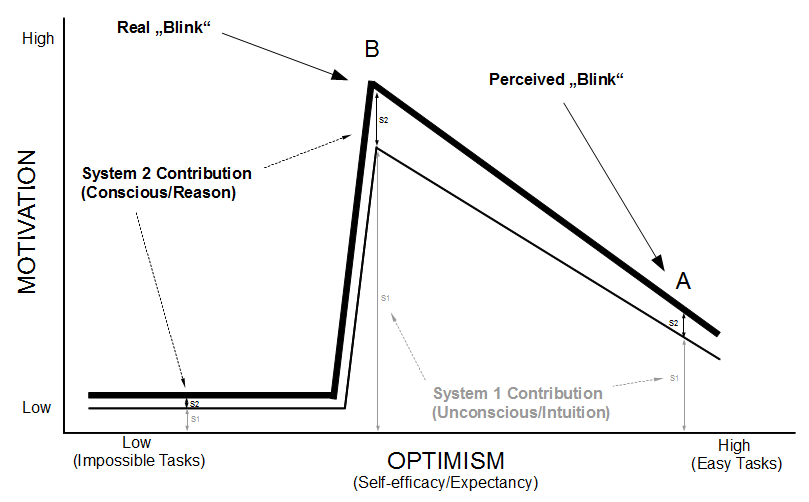

I introduced this article with the statement by Klein (2009), when he refers to “the human-as-hazard model… [and] …the human-as-hero model”. The two models appear to refer very much to the range of perceived high self-efficacy level denoted by point A in Figure 8, where we potentially expect the most skillful and intuitive decisions (by making very good use of skills), as well as the most disastrous (by making no use of skills).

Kahneman & Klein (2009) define it, as the range of “boundary conditions that separate true intuitive skill from overconfident and biased impressions”. The range also relates and is very much connected with our ability to recognize patterns or to make judgments based on an adaptive unconscious (Wilson, 2002).

This is all well and good, and the power and capacity of our System 1 is truly phenomenal, but it is also mystified to the point of being misleading for decision makers.

Malcom Gladwell (2005) in his #1 National Bestseller “Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking” exaggerated the point a little, I believe. Many readers believe, after having read the book, that intuition (Thinking Without Thinking) is so important, that they can easily decide important things without conscious deliberation. You cannot fault the readers for thinking that, as there is a whole school, as mentioned above, “Naturalistic Decision Making Approach” (NDM) (deGroot, 1946/1978 – Chase & Simon, 1973) that can be interpreted that way too.

I am not trying to imply that Gladwell in Blink and NDM are actually making that claim for every decision maker. Many of their examples, related to the adaptive unconscious and NDM, are actually attributed to experts only (chess champions, scientists, firemen, doctors, pilots etc.).

This point is frequently overlooked by the general reader. Also overlooked, is often the fact, that many of the examples deal in fact with high value, i.e. important or difficult decisions like landing a plane with many passengers or deciding how to tackle a big fire.

Here, we are in fact looking at experts, with high self-efficacy level, who are applying their “true intuitive skill”, not at point A in Figure 9 (see below), but at point B. This distinction is very important because it leads to another very common misunderstanding.

As “Blink” suggests, the decision or judgment might be taken without a System 2 contribution (Thinking Without Thinking). This of course is not true. As long as the decider has any concept (CBS=1) of what is going on, or what needs to be decided, there is always a System 2 contribution.

Of course in terms of actual data rate, the contribution of System 2 relative to System 1 might not be very large “…with an estimated 40 pieces a second by the conscious mind… [compared to] … the 11,000,000 pieces of information per second processed by the unconscious mind” (Wilson, 2002), it still matters a great deal.

So it is not the size of the System 2 contribution that matters most, but the type of contribution. In fact, System 2 contribution can have a kind of override function (Evans 2006, Klaczynski & Lavallee 2005, Stanovich 1999). To use the words of Kahneman “System 2 takes over when things get difficult, and it normally has the last word” (Kahneman, 2011) with respect to System 1.

In consequence the impact of System 2 can be (as in this example) that the whole system (or the real decider) has in fact moved from point A to point B in Figure 9, with a respective increase in arousal, decision motivation and allocated resources, to make that decision.

If you look closer at Figure 9, you will in fact notice that at point B, you are actually taking a decision that is more “intuitive” (higher System 1 contribution) than at point A.

Most people would, probably mistakenly, class a decision at point A, as more intuitive, than at point B, because it is easier and has less S2 (System 2), i.e. conscious contribution.

If you think about it, this is not true in dual process theory. It is not a question of either System 1 or System 2 being active, i.e. excluding the activity of one, while the other is active. Both are active and are communicating all the time, and both are most active, as I like to suggest at point B, which is situated nicely at the “self-efficacy or expectancy sweet-spot”.

Here you get the “Real-Blink”, as I like to contend, with the “most intuitive decision”, based on the highest System 1 contribution. Of course it would also be fair to say, that at point B, you are also taking the “most rational decision”.

I believe, both descriptions are correct, and just as valid.

Figure 9: Perceived “Blink” versus Real “Blink” (Schürholz, 2017/2018)

3.2) Strategy to improve decision making under conditions of high self-efficacy

The point that is most important for me to get across, is that under conditions of high self-efficacy, the aspect of goal setting or choosing the appropriate task or decision difficulty, is still led by System 2. Put another way, intuition (System 1) is, to some extent, always guided by System 2. Without the effective “executive role” of System 2, the decider probably operates at point A in Figure 8 (similar to A in Figure 9), trying to deal with as many decisions at the same time, with as little effort, as possible. If that is the case, I suggest a change of strategy and the setting of higher and more difficult goals or decisions.

Only by decreasing the number of (important) decisions, taken at the same time, is the decider able to attempt and set more difficult decision tasks. This strategy increases the motivation and resources available, to tackle fewer, but more difficult decisions, more successfully. It also decreases and moderates the impact of the phenomenon of decision fatigue or ego-depletion (Baumeister et al., 1998 – Muraven & Baumeister, 2000) an effect that arises when taking many decisions in a short period of time.

Learning new decisions and learning new beliefs

As a last topic in this paper, I like to consider the aspects of learning and trying new decisions.

Learning can in fact take place at all points of the spectrum from impossible to easy decisions or tasks. It is important to note though, that the effectiveness and efficiency of learning, will of course vary, depending on your chosen subjective goal or decision difficulty.

We can even learn when we are operating in the area that I have termed “Decision Avoidance” (see Figure 6 above). There we can save resources through the phenomena of status quo bias, omission bias, inaction inertia or choice deferral. We can just wait and take advantage of low arousal, low impulsiveness and low self control effort. Let us assume that at that point, the CBS is switched off i.e. “0”. The system is set to idle. Now learning can start. System 1 and System 2, can respectively begin to scan the incoming “VALUEs (observed)”. The scanning takes the form of comparing incoming data with data stored in memory. The “Concept Belief Switch” (CBS), as introduced above, can be independently moderated and switched (see also Equation 10), by “Self-Efficacy Strength” (largely System 1, “I believe I can” or “I believe I want”) and “Self-Efficacy Level” (largely System 2, “I believe this is me or mine”). Both Systems 1 and 2 keep scanning and finally move into decision mode, when the CBS is switched to “1”. When one CBS is “1”, either System 1 or System 2 has recognized a concept that it sees as valid or desirable.

It is at this point, where not only decision making starts, but also, where real learning can begin, as I like to contend.

Particularly “conscious learning” (System 2 learning) is here of prime or executive importance, as the “Self-Efficacy Level” sets the task or goal difficulty ideally to such a value that “Self-Efficacy Level” is maximum, i.e. the “Self-Efficacy Level” is just reaching the chosen task or decision difficulty (see point B in Figure 6 and point A in Figure 7).

Only under these conditions, is optimal learning and optimal decision making (for important decisions) taking place. Less learning is taking place when the chosen goal is “smaller” than the “Self-Efficacy Level” (see point A and B in Figure 8). Hardly any learning, is taking place when only one of the CBSs is switched “on” and “Impulsiveness” and “Self Control Effort” are low. Only when “Impulsiveness” and “Self Control Effort” start to rise, is learning possible and both CBS switches are likely to overcome their threshold value.

In what other ways are “Impulsiveness” or “Self Control Effort” important in learning?

The way new decisions are taken and new beliefs are learned, is based on the principle that more intense (more motivated, higher arousal) learning and decision making overwrites less intense (less motivated, lower arousal). In that way creating or experiencing new situations, due to say “Impulsiveness”, that are more intense (more motivated, higher arousal), will change the way we see the world and consequently how we react to it.

The nature and direction of our reaction will depend on our ability to set ourselves achievable goals to deal with this new situation.

“Too ambitious goals or decisions” will make us freeze or withdraw. “Too easy goals or decisions” will lead to stagnation. “Positive and achievable goals and decisions” will make us act, advance and grow.

Conclusion and Summary of the “Integrated model for motivation, self-efficacy and decision making”

Decision making and learning, in my understanding, have a number of things in common. It is fair to assume that they use the same processes, and are connected in the way data is stored and retrieved in our brain. They turn situations of uncertainty and belief into certainty and knowing. They transform intention and motivation, into changes of: what we do, who we are and who we will become.

In our development from the simple multicellular organism into the modern homo sapiens sapiens, that we are today, every decision counted and made us who we are now. What we know about ourselves and how we can change, who we like to be, is intrinsically connected to the way we make decisions.

The (ME-DM) model, presented in this paper, contends that a nonmonotonic and discontinuous function best represents the relationship of “motivation and self-efficacy in decision making”.

It suggests that there is an optimal range of self-efficacy level (System 2 Focus) and self-efficacy strength (System 1 Focus), where optimal learning and optimal decision making, for important and irrevocable decisions, is most promising.

To reach, and stay, in this optimal range of self-efficacy appears to require a “strong ego” and an “intelligent and critical” System 2, that chooses its goals wisely.

In the last 70 years, the field of Judgment and Decision Making (JDM) has developed two schools “Heuristics and Biases Approach” (HB) (Meehl, 1954 – Tversky & Kahneman, 1971) and “Naturalistic Decision Making Approach” (NDM) (deGroot, 1946/1978 – Chase & Simon, 1973).

Both schools seem to have focused on different aspects of what we consider today, dual process theory (Evans, 2008). NDM focusing more on System 1, and HB more on System 2.

Following the argument of the paper presented here, with the integrated model for motivation and self-efficacy in decision making (ME-DM), I like to suggest, that possibly, the area of interest that is probably most promising for both schools, is now in fact the same.

It lies, as I like to contend, right in the center of the range of task and decision difficulty, at point B, in Figure 9 (above).

In most areas of our life, we believe an abundance of positive qualities and opportunity is generally good. More skill, more knowledge, more information, more favorable opportunity leads to better outcomes. The above model and research on goal theory and motivation show that this is not generally true. Easier or more is not always better.

The optimum, as so often, lies, as the ME-DM model suggests, in the middle.

References

Ainslie, G. (1992). Picoeconomics: The strategic interaction of successive motivational states within the person. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ainslie, G., & Haslam, N. (1992). Hyperbolic discounting. In G. Loewenstein & J. Elster (Eds.), Choice over time: 57-92. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Akerlof, G. A. (1991). Procrastination and obedience. American Economic Review, 81: 1-19.

Anderson, C. J. (2003). The psychology of doing nothing: forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychological bulletin, 129(1), 139-167

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. HarperCollins

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372.

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 338–375.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A., & Locke, E. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 87–99.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. Journal of Management Vol. 38 No. 1, January 2012 9-44.

Bandura, A. (2015). On Deconstructing Commentaries Regarding Alternative Theories of Self-Regulation. Journal of Management, Vol 41, Issue 4, 2015, 1–20

Bargh, J. A. ( 1989 ). Conditional automaticity: Varieties of automatic influence in social perception and cognition. In J. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), Unintended thought (pp. 3-51 ). New York: Guilford.

Bargh, J. A. (1990). Auto-motives: Preconscious determinants of social interaction. In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition ( Vol. 2, pp. 93-130). New York: Guilford Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego-depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252-1265.

Baumeister, R. F. (2003). The Psychology of Irrationality: Why People Make Foolish, Self-defeating Choices in Brocas, Isabelle; Carrillo, Juan D, The Psychology of Economic Decisions: Rationality and well-being, pp. 1–15

Beach, L. R., & Connolly, T. (2005). The psychology of decision making: People in organizations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Beattie, J., Baron, J., Hershey, J. C., & Spranca, M. D. (1994). Psychological determinants of decision attitude. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 7, 129–144.

Beck, J. W., & Schmidt, A. M. (2011, August). Dynamic test-taking motivation: Effects of self-efficacy on time allocation and performance. In Paper presented at the 71st annual conference of the academy of management, San Antonio, TX.

Beck, J.W., & Schmidt, A.M. (2012). Taken out of context? Cross-level effects of between-person self-efficacy and difficulty on the within-person relationship of self-efficacy with resource allocation and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 119 (2012), 195–208.

Brehm, J. W., & Self, E. (1989). The intensity of motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 109–131.

Carver, C., & Scheier, M. (1998). On the self-regulation of behavior. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). The mind’s eye in chess. In W. G. Chase (Ed.), Visual information processing (pp. 215–281). New York: Academic Press.

Chung, S., & Herrnstein, R. J. (1967). Choice and delay of reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 10: 67-74.

Dhar, R. (1996). The effect of decision strategy on the decision to defer choice. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 9, 265–281.

deGroot, A. D. (1978). Thought and choice in chess. The Hague: Mouton. (Original work published 1946)

Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49, 709-724.

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2003). In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences Vol.7 No.10 October 2003

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2006). The heuristic-analytic theory of reasoning: extension and evaluation. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 13(3):378–95

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2008). Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology. 59:255–78

Gardner, H. ( 1987 ). The mind’s new science. New York: Basic Books.

Gist, M. E. ( 1987 ). Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Academy of Management Review, 12, 472-485.

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17, 183-211.

Gershon, M. D. (1998) The Second Brain. Harper Collins.

Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. Little, Brown and Company.

Higgins, E. T. (1989). Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of selfbeliefs cause people to suffer? In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology ( Vol. 22, pp. 93-136 ). New York: Academic Press.

Izard, C. ( 1993 ). Four systems for emotional activation: Cognitive and noncognitive processes. Psychological Review, 100, 68-90.

Kahneman, D. & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited: attribute substitution in intuitive judgement. In Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment, ed. T Gilovich, D Griffin, D Kahneman, pp. 49–81. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press

Kahneman, D. & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree. American Psychological Association Vol. 64, No. 6, 515–526

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin Books. 23-25. (Kindle E-Book Version)

Kanfer, R. (1990). Motivation theory in I/O psychology. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), The handbook of industrial & organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 75–170). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Academy of Management Review, 29, 440–458.

Kihlstrom, J. F. ( 1987, September 18). The cognitive unconscious. Science, 237, 1445-1552.

Klaczynski, P. A., Lavallee, K. L. (2005). Domain-specific identity, epistemic regulation, and intellectual ability as predictors of belief-biased reasoning: a dual-process perspective. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 92(1):1–24

Klein, G. (2009). Streetlights and shadows : searching for the keys to adapative decision making. MIT Press

Klinger, E. (1975). Consequences of commitment to and disengagement from incentives. Psychological Review, 82, 1-25.

Kukla, A. (1972). Foundations of an attributional theory of performance. Psychological Review, 79, 454–470.

Latham, G.P. & Locke, E.A. (1991), Self-Regulation through Goal Setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 212-247

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Meehl, P. E. (1954). Clinical vs. statistical prediction: A theoretical analysis and a review of the evidence. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Moore, D., & Lowenstein, G. (2004). Self-interest, automaticity, and the psychology of conflict of interest. Social Justice Research, 17(2), 189-202.

Muraven, M. & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-Regulation and Depletion of Limited Resources: Does Self-Control Resemble a Muscle? Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 126, No. 2, 247-259.

Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Olson, J. M., Roese, N. J., & Zanna, M. P. (1996). Expectancies. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 211–238). New York: Guilford Press.

Rao, M. & Gershon, M.D. (2016). The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 13, 517–528 (2016)

Richard, E. M., Diefendorff, J. M., & Martin, J. H. (2006). Revisiting the within-person self-efficacy and performance relation. Human Performance, 19, 67–87.

Ritov, I., & Baron, J. (1992). Status quo and omission biases. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 49–62.

Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 7–59.

Seo, M., & Ilies, R. (2009). The role of self-efficacy, goal, and affect in dynamic motivational self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 109, 120–133.

Schmidt, A. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2009). Prior performance and goal progress as moderators of the relationship between self-efficacy and performance. Human

Performance, 22, 191–203.

Schmidt, A. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2010). The moderating effects of performance ambiguity on the relationship between self-efficacy and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 572–581.

Schürholz, F. (2017). Decision Timing: More Awareness, New Insights, Smarter (Method & Tool assisted decision making). www.decisiontiming.com

Schürholz, F. (2017). An Integrated Model for Motivation and Self-efficacy in Decision Making (ME-DM). Pre-publication Manuscript 19th June 2017, Limited Circulation.

Stanovich, K. E. (1999). Who is Rational? Studies of Individual Differences in Reasoning. Mahwah, NJ: Elrbaum

Steel, P. & König, C. J. (2006). Integrating Theories of Motivation. The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31, No. 4 (Oct., 2006), pp. 889-913

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65-94.

Steel, P. (2011). The Procrastination Equation. Harper.

Stephen M. Collins, S.M., Surette, M. & Bercik, P. (2012). The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nature Reviews Microbiology 10, 735-742 (November 2012)

Tillisch, K., Labus, J., Kilpatrick, L., Jiang, Z., Stains, Ebrat, J. B. , Guyonnet, D, Legrain-Raspaud, S., Trotin,B., Naliboff, B., and Mayer, E. A., (2013). Consumption of Fermented Milk Product With Probiotic Modulates Brain Activity. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jun; 144(7)

Tolli, A. P., & Schmidt, A. M. (2008). The role of feedback, causal attributions, and self-efficacy in goal revision. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 692–701.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1971). Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin, 76, 105–110.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

Tykocinski, O. E., Pittman, T. S., & Tuttle, E. S. (1995). Inaction inertia: Foregoing future benefits as a result of an initial failure to act. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 793–803.

Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., & Williams, A. A. (2001). The changing signs in the relationships among self-efficacy, personal goals, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 605– 620

Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., Tischner, E. C., & Putka, D. J. (2002). Two studies examining the negative effect of self-efficacy on performance.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 506 –516

Vancouver, J. B., & Kendall, L. (2006). When self-efficacy negatively relates to motivation and performance in a learning context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1146 –1153.

Vancouver, J. B., More, K. M., Yoder, R. J. (2008). Self-Efficacy and Resource Allocation: Support for a Nonmonotonic, Discontinuous Model. Journal of Applied Psychology Vol. 93, No. 1, 35–47

Vancouver, J. B. (2012). Rhetorical Reckoning: A Response to Bandura. Journal of Management Vol. 38 No. 2, March 2012, 465-474.

Weinberger, J., & McClelland, D. C. (1990). Cognitive versus traditional motivational models: Irreconcilable or complementary? In E. T. Higgins & R. M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition (Vol. 2, pp. 562-597 ). New York: Guilford Press.

Weiner, B & Kukla, A. (1970). An Attributional Analysis of Achievement Motivation. In Motivational Science: Social and Personality Perspectives edited by Edward Tory Higgins, Arie W. Kruglanski. Psychology Press; 1 edition (August 13, 2000)

Wilson, T.D. (2002). Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Winter, D. G. (1996). Personality: Analysis and interpretation of lives. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wright, R. A., & Brehm, J. W. (1989). Energization and goal attractiveness. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Goal concepts in personality and social psychology (pp. 169–210). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wright, R. A. (1996). Brehm’s theory of motivation as a model of effort and cardiovascular response. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 424–453). New York: Guilford Press.

Yeo, G. B., & Neal, A. (2006). An examination of the dynamic relationship between self-efficacy and performance across levels of analysis and levels of specificity.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1088–1101.

3 thoughts on “An Integrated Model for Motivation and Self-efficacy in Decision Making (ME-DM) – Short Version”

Comments are closed.