There is an in-built mechanism called optimism and overconfidence that lets people believe that they are better, more beautiful, kinder, more intelligent and more skillful than they actually are. While initially comforting for most of us, it is a poor recipe to change things for the better and to realistically improve human decision making in general.

For real change to happen, we should consider and apply more realistic concepts. Unrealistic optimism and overconfidence have prevented us, up to now, to take the important and defining decisions of our lives in a sustainable, truly creative, open or unbiased way. Now, I suggest, it is time to change!

Most people (at least 80%) regularly and systematically overestimate their ability to take important decisions well. Five main illusions or biases of optimism and overconfidence are likely to contribute to and produce this overall effect: a) The illusion of control b) What-you-see-is-all-there-is (WYSIATI, look under optimism and loss aversion in link) c) The superiority illusion (a.k.a. the better than average effect) d) The optimism bias (a.k.a. unrealistic optimism) e) The planning fallacy

“Keeping a clean shirt while eating spaghetti with tomato sauce, is more difficult than you think”: “Real-world example” of the consequences of “Optimism Bias”: , Picture: photobeps

a) Realism in Decision Making

When taking important decisions, we just have to accept that we will, in all likelihood, be subject to the above biases of optimism and overconfidence. Analogous to trying to keep a clean shirt while eating spaghetti with tomato sauce, we should look at ways of how we can minimize or avoid the negative consequences of these biases to get a “clean” or “sustainable” decision.

Of course I am not talking about very small stains of tomato sauce, but in fact about real-world examples of overconfidence. Take the planning fallacy that we are all likely to experience when challenged by a complex decision or when taking on a risky project. A practical example like kitchen remodeling comes to mind. In 2002, a survey of American homeowners found that, on average, households had expected the job to cost $18,658, but in fact, they ended up paying an average of $38,769. (Source: Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, p. 250).

On a larger scale we can see very prominent examples like the Sydney Opera House which cost about 14-times as much as planned or the current construction of the Berlin Brandenburg Airport which is now scheduled to open about 10 years later than previously expected.

Taking the above examples, we can conclude that unrealistic optimism and overconfidence is neither a domain specific phenomenon, nor is it limited to a particular kind of person. It is a general phenomenon!

While as stated above, we have to accept, to a large extent, that these phenomena are always present, with realism, and a proper strategy, we can in fact limit, or sometimes even avoid their negative consequences.

The key to limit or avoid the negative consequences of unrealistic optimism or overconfidence is proper goal setting.

Set yourself realistic yet challenging goals.

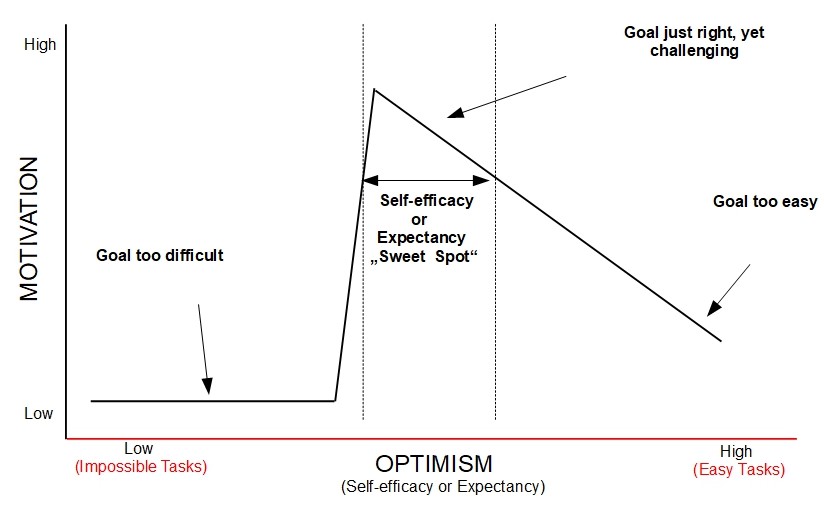

Figure 1: Consciously choose a realistic yet challenging goal or task difficulty on the Optimism/Expectancy/Task axis (Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous Model of Self-efficacy, Schürholz 2017/2018)

Project progression speed or execution speed, for a given task, is usually a very good goal that we can set. To build a modern airport for example, we can assume that 8-10 years is a much more realistic goal than say 5 years, as the overrun of about 10 years for the current Berlin Brandenburg Airport shows. Returning to the example of eating spaghetti with tomato sauce, reducing the eating speed to a moderate level, greatly increases the chance of leaving your lunch time with a clean shirt.

Being able to set a realistic yet challenging goal is of course no small feat. It requires testing, feedback and a calibration process based on real data. Staying with the spaghetti example, you need to determine say the viscosity of the tomato sauce, the bonding of spaghetti to spaghetti, as well as bonding of the sauce to the spaghetti, in order to find a safe, yet practical eating speed.

The data required will of course not appear just by magic. We will have to look for it and we have to be motivated to collect it in the necessary quality.

To sum up the first part of this article, realism in decision making means that

we have to choose and frame our decision and goal wisely. Choosing a realistic yet challenging goal, is our best protection against unrealistic optimism and overconfidence.

b) Realism in Optimism

No-one is exempt from biases of optimism and overconfidence, not even experts like Tali Sharot, as her TED talk below, nicely shows. The only two notable exceptions are people who suffer from depression, or people who actively and systematically apply measures to counter the effects of these biases, as introduced and developed above.

One of the measures, as indicated, to counter these biases, can be, to realistically adjust and set your goal, by taking optimism bias into account. According to Sharot, the British Government did just that by adjusting (i.e. increasing) the budget for the 2012 Olympics in London in line with an expected optimism bias.

This is all well and good when you can increase your budget or lengthen the timeline for your project, but what about cases when you are operating with the wrong tools or an inappropriate concept?

Of course you can only find out whether you have the correct tool (or concept) when you put it to work. (Or using the metaphor of this articel, when you are trying to eat spaghetti with tomato sauce.) Let me apply this problem to the context of decision making.

In decision making, the analogy to the tool or concept would be the appropriate framing of your decision. We therefore have to ask ourselves: Are we correctly defining the question, and are we therefore able to solve the right problem?

There is, of course, no easy answer to this, if we do not check.

Often, we just take things for granted. We also tend to simplify problems to the point where we substitute the original problem by a smaller and easier one without actually realizing. Kahneman calls this effect the substitution bias.

As stated above, even experts on the optimism bias, like Tali Sharot, can be subject to the bias. I have great respect for the work of Tali Sharot and her colleagues, but the TED talk above indicates, that she, as many other people, are probably operating with a concept that is a little oversimplified and only one-dimensional.

Optimism is not a panacea for well-being, success, health and happiness.

Optimism is only the first step that can lead to well-being, success, health and happiness. It can also lead to say risky behavior, financial collapse or faulty planning (as Sharot does mention), or to sum it up more clearly, poor decision making in general.

When one is only concentrating on optimism, I believe, something important is missing, namely the aspect of motivation.

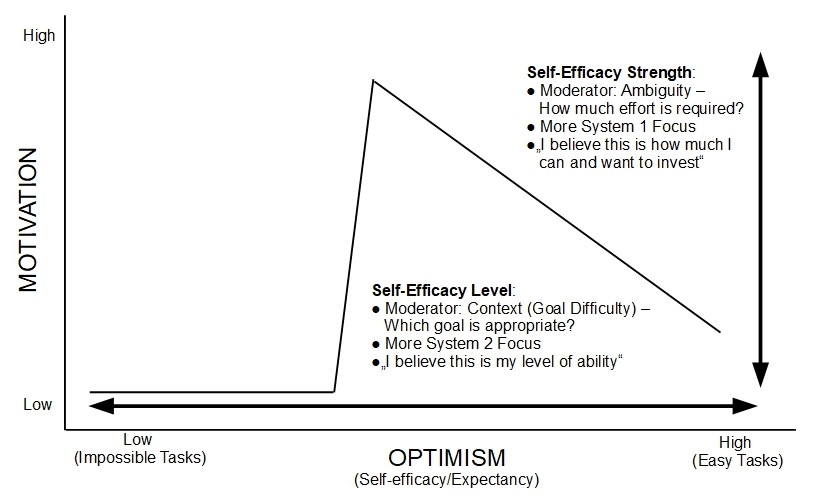

Optimism by itself is just like saying “this is what I want” or less strongly “I believe this is what I want”. It is a belief. It can be a concept, an expectation or a wish (see Self-Efficacy Level in Figure 2, below).

It does not incorporate the aspect of effort, application and all the other important aspects of change energy that come with motivation (see Self-Efficacy Strength in Figure 2, below).

Figure 2: Definition for Self-Efficacy Level and Self-Efficacy Strength (Schürholz, 2017/2018)

To make positive and good use of optimism we clearly need to analyze, determine and state what kind of optimism we are actually dealing with, and how this matches up with a respective motivation or effort.

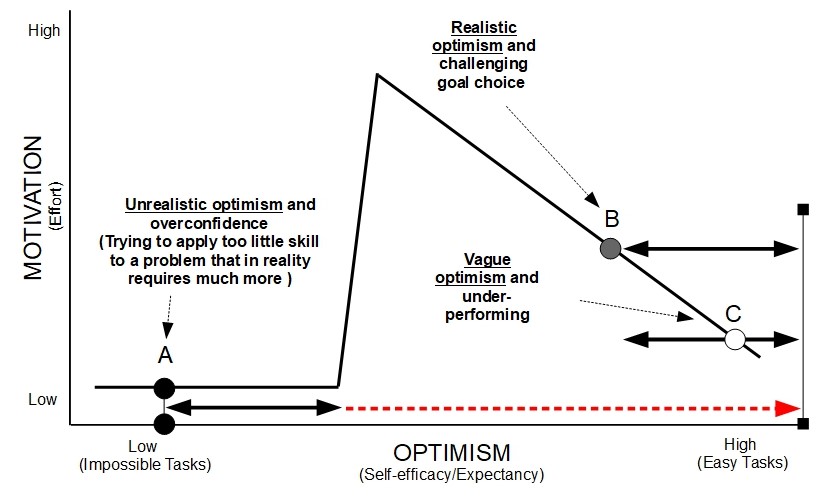

There are of course different kinds and degrees of optimism. Let us consider unrealistic optimism (higher than effective skill), realistic optimism (matching effective skill) and vague optimism (assumed to be lower than effective skill), see Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Varying degrees of “effort” (motivation) for goals with unrealistic, realistic and vague optimism (Schürholz, 2018)

To sum up the second part of this article regarding realism in optimism.

Optimism by itself is neither positive nor negative.

We need to put optimism into a context to be able to qualify it. Building on the Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous Model of Self-efficacy (Figure 1) we can explore how different kinds of optimism affect the respective motivation or effort that we are able to provide (see Figure 3, above).

As it turns out, overconfidence (unrealistic optimism) produces the least effort to reach a goal. Vague optimism effects a slightly larger effort and realistic optimism finally the highest one.

The key to realism in optimism is therefore, to link well defined levels of optimism (Which goal is appropriate?) to the respective values of motivation (How much effort will be invested to achieve that goal?).

Optimism in isolation, can give very little, to no indication, whether well-being, success, health or happiness will result.

c) Realism in Happiness

As presented above, optimism and overconfidence can result in happiness, disaster or anything in between.

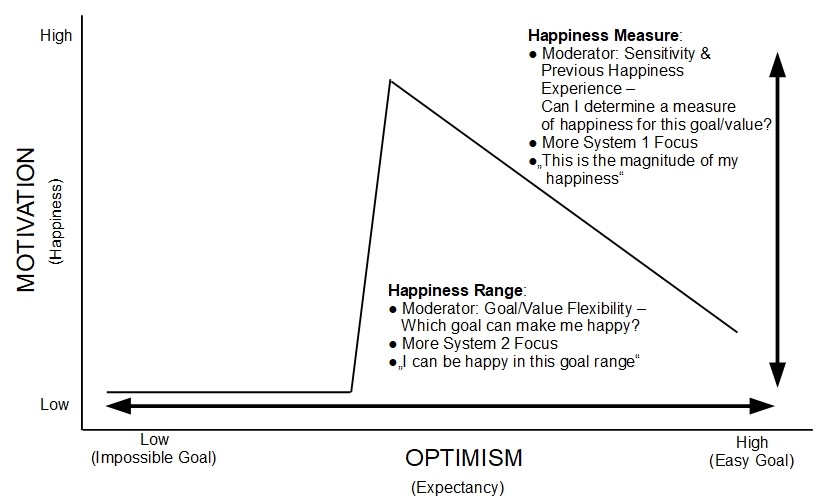

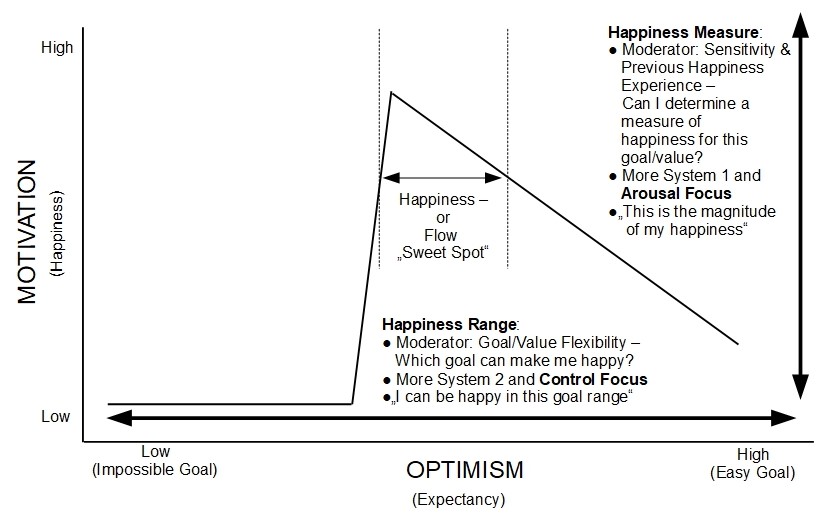

Optimism therefore benefits from being well defined and qualified. Building on this change, I also like to suggest, that happiness ought to be more clearly defined, so that happiness actually becomes a predictable, achievable and measurable concept.

Up to now, happiness is largely a fuzzy concept, as Wikipedia puts it. Here, in this last part of this article, now building on the definition of Self-efficacy in Figure 2 (above), I like to offer a new two-dimensional definition for Happiness (see Figure 4, below). This not only allows happiness to be measured (see vertical dimension “Happiness Measure“), but also encourages everybody to consciously explore and enlarge their happiness range (see horizontal dimension “Happiness Range“).

Figure 4: Definition for Happiness Range and Happiness Measure (Schürholz, 2018)

The quest for happiness probably started with the first organisms on our planet. For human beings, I like to suggest, this quest has been a very long one, and as the picture with the guy trying to eat spaghetti with tomato sauce dramatically shows, has not always been a very easy one.

The reason for this, as I like to propose, is due to the fact that we do not understand properly what happiness is.

Happiness is not a state or a goal. Happiness is in fact an action. Happiness is what we experience when we do something.

Therefore trying to be happy is not only futile, it does not make any sense! We can only experience happiness when we do the the thing (or the things) that make us happy.

At the beginning “not just anything” will make us happy.

We have to find out what is right & appropriate for us.

This means exploration (action), simulation, learning and effort (application).

Not any odd effort will do though!

It needs to be just the right amount of effort.

Not too much and not too little!

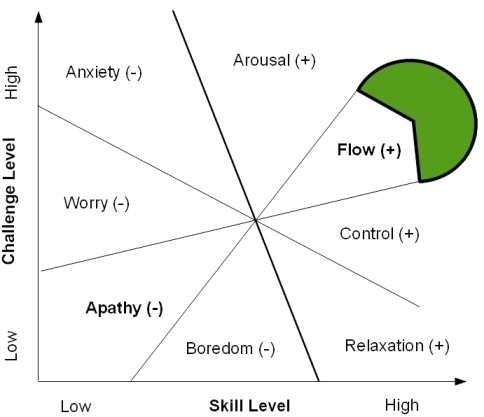

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term “Flow” for it.

It is regarded as a positive mental “state”, (I would prefer the term mental “activity” though), and is defined as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Flow Concept after Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Green limited (area) added by Felix Schürholz

According to Figure 5, flow is positioned just in-between the positive mental states of arousal and control, and opposite to the negative state of apathy.

It is possible to incorporate the flow concept and its respective terms of arousal and control in the two-dimensional definition of happiness (presented here in Figure 4, above), to show the connection of the two concepts. See Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Integrating the Flow Concept in the Definition of Happiness Range and Happiness Measure (Schürholz, 2018)

It is important to note that while Csikszentmihalyi and I are looking at similar scales, with respect to challenge or goal difficulty (as I have termed it), the scales themselves cover a different range. I deduce that Csikszentmihalyi is in fact looking at a more limited range, starting with low challenge and ending in high challenge. The scale I use, is much wider, ranging from easy goals (low challenge) to impossible goals (which could consequently be termed impossible challenges). The use of the latter scale is necessary, to explicitly examine and describe the phenomenon of unrealistic optimism and overconfidence.

Csikszentmihalyi does not describe this phenomenon directly, if at all. He uses indirect mental states like apathy, worry and anxiety to cover some aspects of unrealistic optimism.

It is for this reason that I like to suggest that the definition for happiness and flow, developed here for the first time, in Figure 6, not only represents a more realistic version of happiness, but also a more realistic version of flow.

Unlike Csikszentmihalyi, who seems to suggest, that there is no human limit to increases in challenge, skill and activity, the Nonmonotonic and Discontinuous Model of Self-efficacy (Figure 1) clearly describes and demonstrates that such a limit does in fact exist, for a given situation.

In order to qualify the flow concept, I therefore suggest to add a limited area (similar to the green one, that I have drawn into Figure 5), to indicate that

even flow itself, has in the real world, a practical limitation.

To conclude this article, along with its last aspect of realism in happiness.

In this article, I hope to have shown, that

not only decision making and optimism benefit from more clarity and more realism. Happiness, as might be surprising for many, does as well.

Applying the models and definitions presented here, can contribute to better decision making and more realistic optimism.

In consequence, there is also a very good chance, that we will “act” “realistically” happier by doing so.

There is one last aspect that I like to address, in this article, with respect to happiness.

Happiness is not only something very personal, it is also, in essence, an “internal activity or process”, experienced and carried out by our brain.

It is very noteworthy that it appears to make no difference, for the brain, whether the activity producing happiness is an “outside activity” or whether it is just simulated and experienced internally by the brain. The biochemical processes that take place, are the same.

Now, the practical conclusion that I like to draw from this, is not a philosophical one, but a very real one, particularly when it comes to decision making.

At the end of the day, we have to decide who and what we are.

Are we only algorithms, genes and biochemical processes, or are we human beings with an identity and a purpose?

If we decide that we do have a human identity and purpose then we should act accordingly, and not pretend otherwise.

References

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions. HarperCollins

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 338–375.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A., & Locke, E. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 87–99.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. Journal of Management Vol. 38 No. 1, January 2012 9-44.

Bandura, A. (2015). On Deconstructing Commentaries Regarding Alternative Theories of Self-Regulation. Journal of Management, Vol 41, Issue 4, 2015, 1–20

Beck, J. W., & Schmidt, A. M. (2011, August). Dynamic test-taking motivation: Effects of self-efficacy on time allocation and performance. In Paper presented at the 71st annual conference of the academy of management, San Antonio, TX.

Beck, J.W., & Schmidt, A.M. (2012). Taken out of context? Cross-level effects of between-person self-efficacy and difficulty on the within-person relationship of self-efficacy with resource allocation and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 119 (2012), 195–208.

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Csikszentmihályi, M. (1988), “The flow experience and its significance for human psychology”, in Csikszentmihályi, M., Optimal experience: psychological studies of flow in consciousness, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Csikszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2003). In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences Vol.7 No.10 October 2003

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin Books. (Kindle E-Book Version)

Kukla, A. (1972). Foundations of an attributional theory of performance. Psychological Review, 79, 454–470.

Latham, G.P. & Locke, E.A. (1991), Self-Regulation through Goal Setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 212-247

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schmidt, A. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2009). Prior performance and goal progress as moderators of the relationship between self-efficacy and performance. Human

Performance, 22, 191–203.

Schmidt, A. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2010). The moderating effects of performance ambiguity on the relationship between self-efficacy and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 572–581.

Schürholz, F. (2018). An Integrated Model for Motivation and Self-efficacy in Decision Making (ME-DM). www.decisiontiming.com, PDF

Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology. Volume 21, Issue 23, Pages R941-R945

Steel, P. (2011). The Procrastination Equation. Harper.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., & Williams, A. A. (2001). The changing signs in the relationships among self-efficacy, personal goals, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 605– 620

Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., Tischner, E. C., & Putka, D. J. (2002). Two studies examining the negative effect of self-efficacy on performance.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 506 –516

Vancouver, J. B., & Kendall, L. (2006). When self-efficacy negatively relates to motivation and performance in a learning context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1146 –1153.

Vancouver, J. B., More, K. M., Yoder, R. J. (2008). Self-Efficacy and Resource Allocation: Support for a Nonmonotonic, Discontinuous Model. Journal of Applied Psychology Vol. 93, No. 1, 35–47

Vancouver, J. B. (2012). Rhetorical Reckoning: A Response to Bandura. Journal of Management Vol. 38 No. 2, March 2012, 465-474.

Weiner, B & Kukla, A. (1970). An Attributional Analysis of Achievement Motivation. In Motivational Science: Social and Personality Perspectives edited by Edward Tory Higgins, Arie W. Kruglanski. Psychology Press; 1 edition (August 13, 2000)

Wright, R. A., & Brehm, J. W. (1989). Energization and goal attractiveness. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Goal concepts in personality and social psychology (pp. 169–210). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wright, R. A. (1996). Brehm’s theory of motivation as a model of effort and cardiovascular response. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 424–453). New York: Guilford Press.

Yeo, G. B., & Neal, A. (2006). An examination of the dynamic relationship between self-efficacy and performance across levels of analysis and levels of specificity.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1088–1101.

1 thought on “Time for Realism in Decision Making, Optimism & Happiness”

Comments are closed.